The atomic number uniquely identifies a chemical element. In an atom of neutral charge, atomic number is equal to the number of electrons. The atomic number is closely related to the mass number, which is the number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus of an atom. Highly energetic electrons are bombarded on a target of an element containing 3 0 neutrons. The ratio of radii of nucleus to that of Helium nucleus is ( 1 4 ) 1 / 3. The atomic number of nucleus will be. The number of protons in the nucleus is called the atomic number. The atomic number of each element is unique. The combined number of protons and neutrons in an atom is called the atomic mass number. While the atomic number always stays the same some elements have atoms with different atomic mass numbers.

The atomic number or proton number (symbol Z) of a chemical element is the number of protons found in the nucleus of every atom of that element. The atomic number uniquely identifies a chemical element. It is identical to the charge number of the nucleus. In an uncharged atom, the atomic number is also equal to the number of electrons.

The sum of the atomic number Z and the number of neutronsN gives the mass numberA of an atom. Since protons and neutrons have approximately the same mass (and the mass of the electrons is negligible for many purposes) and the mass defect of nucleon binding is always small compared to the nucleon mass, the atomic mass of any atom, when expressed in unified atomic mass units (making a quantity called the 'relative isotopic mass'), is within 1% of the whole number A.

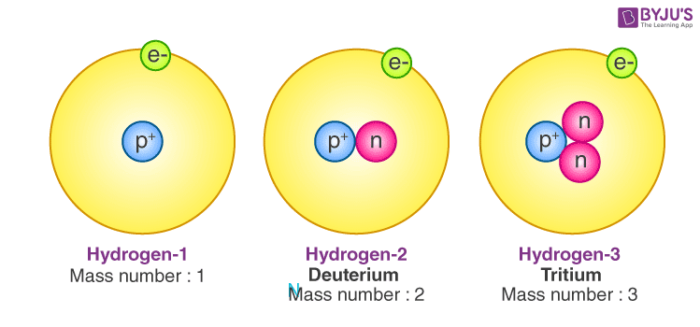

Atoms with the same atomic number but different neutron numbers, and hence different mass numbers, are known as isotopes. A little more than three-quarters of naturally occurring elements exist as a mixture of isotopes (see monoisotopic elements), and the average isotopic mass of an isotopic mixture for an element (called the relative atomic mass) in a defined environment on Earth, determines the element's standard atomic weight. Historically, it was these atomic weights of elements (in comparison to hydrogen) that were the quantities measurable by chemists in the 19th century.

The conventional symbol Z comes from the German word Zahl meaning number, which, before the modern synthesis of ideas from chemistry and physics, merely denoted an element's numerical place in the periodic table, whose order is approximately, but not completely, consistent with the order of the elements by atomic weights. Only after 1915, with the suggestion and evidence that this Z number was also the nuclear charge and a physical characteristic of atoms, did the word Atomzahl (and its English equivalent atomic number) come into common use in this context.

History[edit]

The periodic table and a natural number for each element[edit]

Loosely speaking, the existence or construction of a periodic table of elements creates an ordering of the elements, and so they can be numbered in order.

Dmitri Mendeleev claimed that he arranged his first periodic tables (first published on March 6, 1869) in order of atomic weight ('Atomgewicht').[1] However, in consideration of the elements' observed chemical properties, he changed the order slightly and placed tellurium (atomic weight 127.6) ahead of iodine (atomic weight 126.9).[1][2] This placement is consistent with the modern practice of ordering the elements by proton number, Z, but that number was not known or suspected at the time.

A simple numbering based on periodic table position was never entirely satisfactory, however. Besides the case of iodine and tellurium, later several other pairs of elements (such as argon and potassium, cobalt and nickel) were known to have nearly identical or reversed atomic weights, thus requiring their placement in the periodic table to be determined by their chemical properties. However the gradual identification of more and more chemically similar lanthanide elements, whose atomic number was not obvious, led to inconsistency and uncertainty in the periodic numbering of elements at least from lutetium (element 71) onward (hafnium was not known at this time).

The Rutherford-Bohr model and van den Broek[edit]

In 1911, Ernest Rutherford gave a model of the atom in which a central nucleus held most of the atom's mass and a positive charge which, in units of the electron's charge, was to be approximately equal to half of the atom's atomic weight, expressed in numbers of hydrogen atoms. This central charge would thus be approximately half the atomic weight (though it was almost 25% different from the atomic number of gold (Z = 79, A = 197), the single element from which Rutherford made his guess). Nevertheless, in spite of Rutherford's estimation that gold had a central charge of about 100 (but was element Z = 79 on the periodic table), a month after Rutherford's paper appeared, Antonius van den Broek first formally suggested that the central charge and number of electrons in an atom was exactly equal to its place in the periodic table (also known as element number, atomic number, and symbolized Z). This proved eventually to be the case.

Moseley's 1913 experiment[edit]

The experimental position improved dramatically after research by Henry Moseley in 1913.[3] Moseley, after discussions with Bohr who was at the same lab (and who had used Van den Broek's hypothesis in his Bohr model of the atom), decided to test Van den Broek's and Bohr's hypothesis directly, by seeing if spectral lines emitted from excited atoms fitted the Bohr theory's postulation that the frequency of the spectral lines be proportional to the square of Z.

To do this, Moseley measured the wavelengths of the innermost photon transitions (K and L lines) produced by the elements from aluminum (Z = 13) to gold (Z = 79) used as a series of movable anodic targets inside an x-ray tube.[4] The square root of the frequency of these photons (x-rays) increased from one target to the next in an arithmetic progression. This led to the conclusion (Moseley's law) that the atomic number does closely correspond (with an offset of one unit for K-lines, in Moseley's work) to the calculated electric charge of the nucleus, i.e. the element number Z. Among other things, Moseley demonstrated that the lanthanide series (from lanthanum to lutetium inclusive) must have 15 members—no fewer and no more—which was far from obvious from known chemistry at that time.

Missing elements[edit]

After Moseley's death in 1915, the atomic numbers of all known elements from hydrogen to uranium (Z = 92) were examined by his method. There were seven elements (with Z < 92) which were not found and therefore identified as still undiscovered, corresponding to atomic numbers 43, 61, 72, 75, 85, 87 and 91.[5] From 1918 to 1947, all seven of these missing elements were discovered.[6] By this time, the first four transuranium elements had also been discovered, so that the periodic table was complete with no gaps as far as curium (Z = 96).

The proton and the idea of nuclear electrons[edit]

In 1915, the reason for nuclear charge being quantized in units of Z, which were now recognized to be the same as the element number, was not understood. An old idea called Prout's hypothesis had postulated that the elements were all made of residues (or 'protyles') of the lightest element hydrogen, which in the Bohr-Rutherford model had a single electron and a nuclear charge of one. However, as early as 1907, Rutherford and Thomas Royds had shown that alpha particles, which had a charge of +2, were the nuclei of helium atoms, which had a mass four times that of hydrogen, not two times. If Prout's hypothesis were true, something had to be neutralizing some of the charge of the hydrogen nuclei present in the nuclei of heavier atoms.

In 1917, Rutherford succeeded in generating hydrogen nuclei from a nuclear reaction between alpha particles and nitrogen gas,[7] and believed he had proven Prout's law. He called the new heavy nuclear particles protons in 1920 (alternate names being proutons and protyles). It had been immediately apparent from the work of Moseley that the nuclei of heavy atoms have more than twice as much mass as would be expected from their being made of hydrogen nuclei, and thus there was required a hypothesis for the neutralization of the extra protons presumed present in all heavy nuclei. A helium nucleus was presumed to be composed of four protons plus two 'nuclear electrons' (electrons bound inside the nucleus) to cancel two of the charges. At the other end of the periodic table, a nucleus of gold with a mass 197 times that of hydrogen was thought to contain 118 nuclear electrons in the nucleus to give it a residual charge of +79, consistent with its atomic number.

The discovery of the neutron makes Z the proton number[edit]

All consideration of nuclear electrons ended with James Chadwick's discovery of the neutron in 1932. An atom of gold now was seen as containing 118 neutrons rather than 118 nuclear electrons, and its positive charge now was realized to come entirely from a content of 79 protons. After 1932, therefore, an element's atomic number Z was also realized to be identical to the proton number of its nuclei.

The symbol of Z[edit]

The conventional symbol Z possibly comes from the German word Atomzahl (atomic number).[8] However, prior to 1915, the word Zahl (simply number) was used for an element's assigned number in the periodic table.

Chemical properties[edit]

Each element has a specific set of chemical properties as a consequence of the number of electrons present in the neutral atom, which is Z (the atomic number). The configuration of these electrons follows from the principles of quantum mechanics. The number of electrons in each element's electron shells, particularly the outermost valence shell, is the primary factor in determining its chemical bonding behavior. Hence, it is the atomic number alone that determines the chemical properties of an element; and it is for this reason that an element can be defined as consisting of any mixture of atoms with a given atomic number.

New elements[edit]

The quest for new elements is usually described using atomic numbers. As of 2021, all elements with atomic numbers 1 to 118 have been observed. Synthesis of new elements is accomplished by bombarding target atoms of heavy elements with ions, such that the sum of the atomic numbers of the target and ion elements equals the atomic number of the element being created. In general, the half-life of a nuclide becomes shorter as atomic number increases, though undiscovered nuclides with certain 'magic' numbers of protons and neutrons may have relatively longer half-lives and comprise an island of stability.

See also[edit]

| Look up atomic number in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

References[edit]

- ^ abThe Periodic Table of Elements, American Institute of Physics

- ^The Development of the Periodic Table, Royal Society of Chemistry

- ^Ordering the Elements in the Periodic Table, Royal Chemical Society

- ^Moseley, H.G.J. (1913). 'XCIII.The high-frequency spectra of the elements'. Philosophical Magazine. Series 6. 26 (156): 1024. doi:10.1080/14786441308635052. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010.

- ^Eric Scerri, A tale of seven elements, (Oxford University Press 2013) ISBN978-0-19-539131-2, p.47

- ^Scerri chaps. 3–9 (one chapter per element)

- ^Ernest Rutherford | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online. Nzhistory.net.nz (19 October 1937). Retrieved on 2011-01-26.

- ^Origin of symbol Z. frostburg.edu

Atomic Mass

Atomic mass is based on a relative scale and the mass of 12C (carbon twelve) is defined as 12 amu.

Why do we specify 12C? We do not simply state the the mass of a C atom is 12 amu because elements exist as a variety of isotopes.

Carbon exists as two major isotopes, 12C, and 13C (14C exists and has a half life of 5730 y, 10C and 11C also exist; their half lives are 19.45 min and 20.3 days respectively). Each carbon atom has the same number of protons and electrons, 6. 12C has 6 neutrons, 13C has 7 neutrons, and 14C has 8 neutrons and so on. Since there are a variety of carbon isotopes we must specify which C atom defines the scale.

All the masses of the elements are determined relative to 12C.

By the way, the mass of an element is not equal to the sum of the masses of the subatomic particles of which the element is made!

Average Atomic Mass

Since many elements have a number of isotopes, and since chemists rarely work with one atom at a time, chemists use average atomic mass.

On the periodic table the mass of carbon is reported as 12.01 amu. This is the average atomic mass of carbon. No single carbon atom has a mass of 12.01 amu, but in a handful of C atoms the average mass of the carbon atoms is 12.01 amu.

Why 12.01 amu?

If a sample of carbon was placed in amass spectrometer the spectrometer would detect two different C atoms, 12C and 13C.

The natural abundances of 14C, 10C and 11C are so low that most mass spectrometers cannot detect the effect these isotopes have on the average mass. 14C dating is accomplished by measuring the radioactivity of a sample, not by actually counting the number of 14C atoms.

The average mass of a carbon is calculated from the information the mass spectrometer collects.

The mass spectrometer reports that there are two isotopes of carbon,

98.99% of the sample has a mass of 12 amu (not a surprise since this is the atom on which the scale is based).1.11% of the sample has a mass of 13.003355 amu (this isotope is 1.0836129 times as massive as 12C)

The average mass is simply a weighted average.

ave. mass = 12.01 amu

(Yes, the number 12.01 has the right number of significant figures, even though 1.11% only has 3 significant figures.)

If we know the natural abundance (the natural abundance of an isotope of an element is the percent of that isotope as it occurs in a sample on earth) of all the isotopes and the mass of all the isotopes we can find the average atomic mass. The average atomic mass is simply a weighted average of the masses of all the isotopes.

(Yes, the sig figs are correct.)

Another kind of question could be asked...

Copper has two isotopes 63Cu and 65Cu. The atomic mass of copper is 63.54. The atomic masses of 63Cu and 65Cu are 62.9296 and 64.9278 amu respectively; what is the natural abundance of each isotope?

substituting gives

One equation and two unknowns...is there another equation? If there is another equation we would have two equations and two unknowns, and a system of two equations and two unknowns is solvable.

Since there are only two major isotopes of Cu we know that

or

(eq. B)

Use eq. B to substitute for %63Cu in eq. A.

To the correct number of significant figures

Of course, a question like the one above could be turned around another way.

Gallium, atomic mass 69.72 amu, has two major isotopes, 69Ga, atomic mass 68.9257 amu, and 71Ga. If the natural abundance of each isotope is 60.00 and 40.00 % respectively what is the mass (in amu) of 71Ga.

The mole

What is the relative mass of 1 C atom as compared to 1 H atom?

The Mass Number Of An Element Is Equal To The

What is the relative mass of 100 C atoms as compared to 100 H atoms?

The Mass Number Of An Element Is Equal To __

What is the relative mass of 1 W atom as compared to 1 H atom?

What is the relative mass of 100 W atoms as compared to 100 H atoms?

The point here? As long as the number of atoms remains the same the relative mass does not change.

Atoms are small, and it is possible to place 1.0079 g of H on a balance (possible but not easy in the case of hydrogen).

It is also possible to place 183.9 g W, or 12.01 g of C on a balance.

The Mass Number Of An Element Is Equal To Quizlet

Now, I state with absolute certainty that I have placed the same number of atoms on each balance! How do I know? I know because the relative masses of the samples on the balance, are the same as the relative masses of the individual atoms.

How Is The Mass Number Determined

W:H = (183.9 g/1.0079 g):1 = 182:1C:H = (12.01 g/1.0079 g):1 = 11.92:1

The number of atoms I placed on the balance is know as a mole.

For many years the number of atoms in a mole remained unknown; however, now it is know that a mole of atoms contains 6.02214 x 1023 atoms.

So, the periodic table provides us with a great deal of information.

The periodic table lists

The Mass Number Of An Atom Is Equal To

the mass of an atom in amu,An Example Of An Element

the mass of a mole of atoms (i.e. the molar mass) in grams,

and the mass of 6.02214 x 1023 atoms in grams

The atomic mass of C is 12.01 amu. What is the mass of 1 C atom?